“We shouldn’t regulate too early and before we understand what the service design is going to look like,” he told a global audience of UAM industry, local authorities and regulators. “It is very early to say we know what the public wants, we have to give them an opportunity to decide for themselves.” There are ways in which the regulator can use its current powers to support locally-developed transport infrastructures – but these are all based on existing technologies and business models and it is not yet clear what the future technologies and business models are going to be. “Therefore we have to find as much space as possible for the those technologies to be safely trialled, ” he told attendees.

The correct sequence is first to go for public acceptance while simultaneously working on the legal framework, said Dr Georgi Georgiev, Business Development Partner with robots.expert. “The city needs to get into its own hands not only the local regulation but also the process management of integration of that kind of mobility.” Every city is different and it will be important to develop the eco-system based on actual demand and circumstances “and only afterwards begin to clothe that body with regulatory and legislative clothes,” he said. “We want an alignment of a holistic approach valid for cities around the world but our cities are so unique in responding to local demands, needs and mentality that we can never standardise it completely and it would be wrong to do that.”

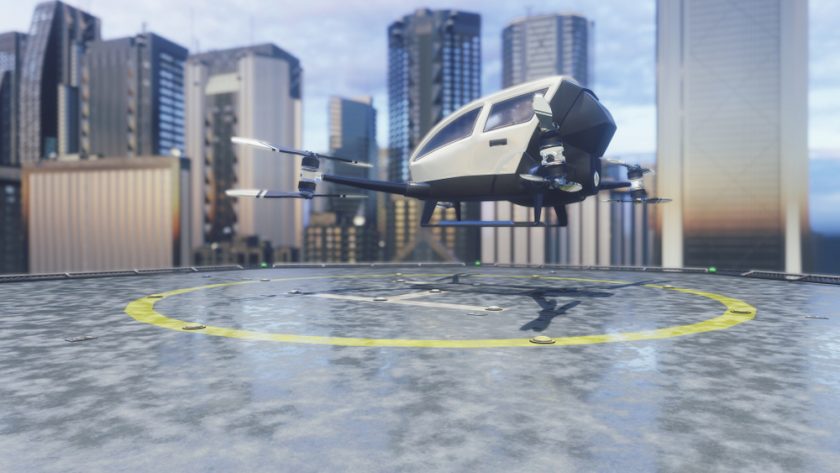

The City State of Hamburg – one of the few cities in Europe to have autonomous control of its airspace – has already begun the process of planning UAM services based on the identified priorities of its inhabitants. “If we want to implement drones in Hamburg it must be publicly accepted and we need to find ways to balances corporate and public interests,” said Franziska Biermann of the Hamburg State Economy and Innovation Agency. “But citizens are still hesitant, though it depends on what questions you ask. If you ask: “Do you want to travel from the city to the airport?” people say “Yes”. But if ask “Do you want passenger drones flying above your head?” they say “No”. We have started with a project ferrying medical goods and for that there is acceptance, but for passenger and maybe large freight transport there won’t be public acceptance for the moment.”

In Europe, the new U-space regulation (https://www.unmannedairspace.info/emerging-regulations/the-european-commission-adopts-the-u-space-package-finally/) which will come into force in January 2023 will be challenging for the city to implement, making sure it has all the right legal instruments to implement and the resources to deal with the environmental issues.

The attitude towards innovation has changed since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Gary Cutts, Challenge Director at the UK government’s Future Flight Research and Innovation programme. “You can’t see urban air mobility as an aviation-only issue; it is part of a multi modal transport system with a lot of new entrants. The speed of development is very different, with hundreds of people who want to do things in the one- to two-year horizon.”

“There’s a strong and important role for local communities to be consulted in a formal sense to try to implement the service they want in their locality,” said David Tait. “This takes place in a globalised eco system regulated to maintain the safety of passengers, uninvolved their parties and other airspace users. There has to be an element of testing and trialling to establish what services will be offered for the public to look like.”

(Image: Shuttertstock/ Design Projects)