By Pawel Korzec Co-founder and CEO at DroneRadar. First published in www.droneradar.eu – republished with kind permission.

First, we’d like to underline the fact, that without detailed spectrum analyses, it is difficult to judge if you witnessed jamming or spoofing. However, there are circumstantial evidence that will help understand the issue and identify the causes of the drone’s “strange” or “escaping” behaviour.

This article was inspired by few posts that appeared shortly after New Year’s on popular social media channels (spelling is original): “Orlando Drone Show disrupted”, “Hundreds of drones plunged into the water” “Yesterday around 5 PM in Rumia (in Pomerania), DJI Mini 4 Pro. About 15 seconds after takeoff, the drone started flying in any direction at a very high speed. It was around 30 meters above the ground, there was practically no wind, no rain, the Kp index was low, before takeoff the drone connected to all satellites, the signal was fine, and the temperature was above freezing. It didn’t crash because the propellers were intact after a hard landing with momentum in the neighbor’s tree (fortunately it landed safely and didn’t cause any damage). Only one arm was broken, and there were some scratches and minor damages. What could be the cause? Was it some error? Everything seemed normal. During the flight, the drone turned around at some point but still had no control. It kept descending even though I was instructing it to go higher. I’ve been flying DJI drones for years, and this is the first time I encountered such a situation.” “Hi, does anyone from around Elbląg (also Pomerania in Poland) fly drones? I’m asking because I’m experiencing GPS signal loss. When I raise the drone to 120m, I lose the signal. Below that height, it’s fine. DJI Air 3.”

Before we explain the issue, please note that what we write here is based on the knowledge and experience we’ve gathered so far. The information is true at the time of writing this article (early 2025), but it may become outdated at any time.

When we mention GNSS, we refer to the following constellations/systems: GPS (US), Galileo (European), BeiDou (Chinese), and GLONASS (Russian). GNSS Jamming is signal interference, while spoofing is manipulating the signal to alter position and/or time.

Due to resources, we limited our tests to DJI drones only. We briefly tested other drones, including those used during drone shows. These proved more resistant to jamming and spoofing, but we will write about them in a separate article.

How does a jammed DJI drone behave?

We’ve conducted tests with various jamming scenarios and different types of DJI drones. The result?

The drone behaves exactly as described in the social media post. It suddenly flies in any direction, constantly increasing or decreasing altitude, while noticeable rising the speed. Switching to manual control temporarily solves the problem. However, the real issue is that while jamming affects the GNSS chipset immediately, it takes much longer for the drone to return to “normal”, usually around 60-90 seconds. And this “short infection” is the biggest challenge. Why? It only takes a brief moment to be affected by jamming, and approx 60s to recover.

Also, please remember that most DJI drones rely on vision-based and inertial systems, so their behaviour at different heights may vary. Generally, up to a height of 10m from take-off, newer DJI drones show little susceptibility to jamming. Keep this in mind as a risk mitigation strategy. If you can safely descend to a height where the vision-based navigation system takes over, you should regain control. But, as always, proceed with caution—the “jammed” drone might be moving too fast for that 10m altitude to be sufficient to stop it.

How does jamming look on the GSC?

On the control panel (Ground Station Control) you will see a loss of GNSS (GPS) signal. The number of satellites icon will turn red, although it may be orange at times.

How does a spoofed DJI drone behave?

Essentially, similar to a jamming-affected drone, but with more “stability” in flight. Typically, it flies in the desired direction and changes altitude “more slowly” than a jammed one. Of course, this is subjective and hard to identify definitively at first. The only relatively “sure” difference is that with spoofing, you’ll still be within GNSS signal range, so the satellite icon will likely be white, but showing fewer available satellites (e.g., from 23 to 12). But who constantly look at that indicator…?

Please remember, spoofing is a more complex issue than jamming. To perform advanced spoofing without even noticing the loss of a GPS fix, equipment worth at least EUR1,000 to 3,000+ is needed. This requires some advanced knowledge of spoofing, antennas for different frequency ranges, and various constellations.

In summary, spoofing is technically possible but complex and not something that can be done easily at no cost. It requires more preparation. DJI drones showed greater resistance to less advanced spoofing methods, like when jamming is first applied and then new satellites are “inserted” (e.g., “non-coherent” spoofing). The tested models were resistant to this attack, simply losing the fix, similar to jamming.

Geopolitical Situation

Both of the above social media posts are from areas relatively close to the Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia). It’s been known for months that Kaliningrad is a source of GNSS interference. While initially, it was mainly jamming, since October-November 2024, more sophisticated spoofing methods have been observed. This situation seems to give a clear answer to what happened to the mentioned users… But!

In the area of the bay (of Gdańsk) itself, we have installed the TERRESTRIAL GNSS anomaly detection system (for detection and classification of GNSS jamming and spoofing). Our tests showed that even the most aggressive attacks from Russia do not necessary reach the ground. Russian jamming antennas are likely directional, designed to effectively disrupt aircraft at higher altitudes (much above 120m). City of Rumia, in our example, is slightly higher than our sensor (around 30-60m AGL). Additionally, the flight at around 24m altitude may have been enough to catch the interference.

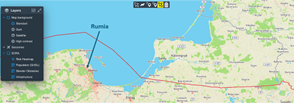

City of Rumia. Social Media User’s Case. View from the GP-CLOUD App (GPSPATRON)

In conclusion, we observed minimal GPS signal degradation in the Bay of Gdańsk, but it was so small that where we tested it, it could be classified as “ordinary” industrial interference. However, we emphasise that this may be due to the position of the sensor and the considerable distance between our sensor and the flight location in Rumia. But was it interference from Kaliningrad? We can’t say with 100% certainty. It’s more likely only around 30%.

Below, we present a screenshot from our sensor (GP-CLOUD from GPSPATRON) during the flight described in the social media posts.

Fun, stupidity, unawareness, or trying to fool the boss, employer, or endangering national security?

Just as it was once popular to shine powerful lasers in pilots’ eyes (a completely reprehensible behaviour), now we observe an increasing number of hooligans/idiots, either aware or unaware of their actions, playing with cheap jammers. “Cheap” means devices costing as little as a few dozen of Euro, available on popular sales platforms (we deliberately avoid publishing example links). Another group that may cause interference are professional drivers (trucks and taxi drivers). Why do they do this? The simplest answer: to avoid being “tracked” in the system. There are also thieves, especially those stealing expensive cars. From our observations, they use high-power jammers, thus having a larger range.

Lastly, there are the state services (In Poland we call them three letters services). It’s known that they use jammers, but they won’t admit how, where, or when.

In summary, you can relatively often expect jamming near roads, “strong” jamming near expressways and highways, and irresponsible people playing with GNSS interference everywhere. As a reminder, interfering with protected frequencies is prohibited, but more on that in a future article.

Websites like gpsjam.org, spoofing.skai-data-services.com, flightradar24, and similar

The biggest advantage of these services is that they present anomalies in an understandable form. This apparent ease of understanding and interpreting maps has a certain limitation. And it is significant, because these maps cannot be used for jamming on the ground and at very low altitudes. It’s important to remember that the maps from gpsjam and spoofing.skai-data-services.com have serious limitations.

The data powering these portals comes from the ADS-B standard, and the aircraft providing this information usually fly at high altitudes (up to 11km above the ground). Therefore, the visualisations in these services cannot be directly related to terrestrial GNSS disturbances at lower altitudes (e.g., 120m AGL).

A few words about ADS-B and its usefulness in detecting GNSS anomalies

The principle behind ADS-B is relatively simple. Aircraft (and not only them) equipped with this system continuously send their position in a “broadcasting” mode. In parallel, they also send a variety of other data, including information about uncertainty, accuracy, and integrity of data from onboard devices, including satellite receivers. Unfortunately, in the standardisation area, there is considerable chaos. In simple terms, there are several types of data quality indicators in the ADS-B system, including:

- Uncertainty indicators

- Accuracy indicators

- Integrity indicators

To sum up, ADS-B contains many parameters that define the quality of the data in positional reports. It is difficult to deduce the precious type and source of GNSS interference just from these indicators.

The mentioned services work by aggregating data from multiple sources.

Therefore, only similarly “bad” data from several aircraft can confirm a theory of an anomaly and create color-coded markers on the maps of these services. It’s important to note that these maps are not live, but rather semi-live. The system generally requires historical data to display information.

With each version evolution of ADS-B, these parameters are often renamed or redefined. These updates complicate understanding and analysing the uncertainty in interpreting ADS-B data.

But thanks to the great effort of those services authors, we have proof that anomalies and hacker attacks occur in the airspace.

Finally, what’s most likely when a drone behaves strangely?

According to our observations, the most likely scenario is intentional or unintentional use of jammers, which can be bought for just a few dozen euro/dollars.

Be prepared for a prank or joke. Small USB-sized jammers with relatively low power (measured in mW) can interfere with a receiver in a direct line of sight (line of sight) up to a few hundred meters. To illustrate how “weak” the GPS signal is, imagine trying to spot a light bulb from several hundred kilometres away.

Naturally, hybrid actions from aggressors may also be likely, especially in the areas around Kaliningrad, Brest, and Ukraine. But those can be also met, by aggressor in any place of world as a part of the hybrid war.

Our observations also show that professional drones used during drone shows (drone swarms) are much more resistant to interference. They use different constellations, supported by different Galileo frequencies (E5a/E5b, E6, E1), GPS (L5, L2, L1) and GLONASS (G3, G2, G1). Our experience shows that attacking them is much more demanding, expensive, requires installing infrastructure on the ground, sometimes in the air, but it is completely POSSIBLE.

It’s also possible that natural factors, such as solar eruptions (high Kp index), unfavourable constellation arrangements, or signal reflections from obstacles, could degrade GNSS signals.

So is there an antidote?

It’s hard to say. In order to keep the article relatively short, we have deliberately not touched upon the issues of counteracting jamming and spoofing. There are methods of protection using special antennas, systems, authentication and authorization, such as for example Galileo OSNMA (Open Service Navigation Message Authentication). But more on that in subsequent articles.

So what can be done now?

The answer is simple. There are two ways that can be done now at a relatively low cost:

The first is to check the susceptibility of your systems (drones) to various interferences: jamming and spoofing. Together with GPSPATRON, we can help you conduct such tests. From the simplest to the most advanced using virtually every constellation and their combination. Such a test will probably take two days, but it is better to know than to be surprised by a hacker.

The second thing is to provide a system for monitoring and classification of GNSS signal anomalies during flights and drone shows. We have been providing such services for several months for now. The purpose of monitoring is to obtain evidence that the drones did not fly where they were supposed to NOT BECAUSE OF US. In other word, we can provide a proof that IT WAS NOT YOUR FAULT. This evidence is the recorded in the system. As part of such monitoring, you will receive electronically recorded evidence that you can use in court in the event of lawsuits. In our opinion, providing monitoring of anomalies during flights is mandatory.

For more information

https://www.droneradar.eu/post/how-to-recognise-if-a-drone-has-been-jammed-or-spoofed-during-flight