By Philip Butterworth-Hayes

We are at least eighteen months away from the next generation of drone threats appearing on the battlefield, according to drone defence experts attending the Defence & Security Equipment International (DSEI) show last week in London.

We are still in the fourth stage of the drone war in Ukraine. As we reported in July this year, stage one was characterised by Ukraine’s successful use of drones – symbolised by the Bayraktar TB2 and innovative use of small, commercially available drones armed with mortar bombs for precision attacks – in repelling the initial Russian invasion. Stage Two was Russia’s reply: extensive use of Shahed 136/Geran-2 drones in swarming attacks on Ukrainian towns and cities. Stage Three saw a massive escalation in commercial drones by both sides for a wide number of roles, and Stage Four has the seen the widespread deployment of first-person-view (FPV) drones, loitering munitions and “kamikaze” drones in increasingly effective precision attacks. As we reported earlier this year, the Mavic 3 Enterprise E/T is probably now the most ubiquitous drone flying in Ukraine.

For the moment, most small drone air defence systems rely on RF frequency detection and jamming/spoofing, where is a close match between the offensive and defensive technology and affordability metrics. The danger, for the defenders, is when a gap starts to appear between defensive and offensive technology and affordability match-ups.

Over the horizon lies the next generation of threat which will not be countered by RF based detection and jamming/spoofing defences: affordable, micro-tactical loitering munitions in paired or swarm configurations, where one drone acts as a target designator and is networked with other drones in the attack role.

How will it possible to deploy an effective and affordable range of counter-UAS technologies against this over-the-horizon threat – where inertial navigation systems and a minimal connection between platform and pilot will make these drones virtually autonomous and therefore blind to current generation RF sensors? Widespread use of open-source materials and components will also make them increasingly affordable and therefore ubiquitous.

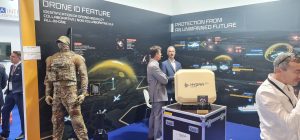

To match this threat here will need to be a new generation of proportionately small, affordable tactical radars integrated with a new range of kinetic responses – such as the short-range Interceptor-SR launched by MARSS at the show. Affordability and mass production will be vital.

According to a range of drone technology experts, talking to Unmanned Airspace during DSEI, Russia is still some way away from deploying this new generation of technologies in Ukraine.

“We are starting to see inertial navigation systems used on some long-range drones but these are still few and far between. We haven’t seen INS embedded in any tactical systems, yet.” said one C-UAS equipment supplier to Ukraine.

“It is very, very rare to see a totally autonomous command and control system,” said another,” and we are working to make sure even the slightest signal emissions will become visible.

For the moment, Russia appears to be focusing on improving its tactical deployment of commercial drones for military operations and investing in more capable long range drone technologies rather than fast-tracking affordable, tactical, AI-based drone swarm technologies at scale. Russia’s current focus is on developing more capable versions of current service types at scale, rather than deploying new AI-based tactical systems.

Although surprises are always possible.

According to a September article from the Jamestown Foundation Research think-tank:

“On June 28, the Russian government approved the “Development Strategy for Unmanned Aviation Until 2030” (Government.ru, June 28)…The document primarily lays out the basic scenario for future development and production in Russia’s drone industry… The planned number of drones to be produced in 2023–2026 stands at 52,100, with the average annual production rate exceeding 13,000; 105,500 in 2027–2030, with the average annual rate exceeding 26,000; and 177,700 in 2031–2035, with the average annual production rate exceeding 35,500 (Government.ru, June 28).

“The projected numbers for drone industry employees are rather unrealistic. The projected production rates signals that the Russian government does not plan to create a Russian counterpart to the Chinese company DJI, which sells millions of small consumer drones every year….However, Moscow’s existing deficit of adequate financial sources, technologies, equipment and human capital hurt its ambitions. And these deficits coupled with Russia being cut-off from industrial cooperation with many developed countries due to Western sanctions make this model non-sustainable in terms of material outcomes.”

What this could mean, however, is that if Ukraine can obtain affordable, tactical, AI-based drone swarm technologies from the West there is an opportunity, for the first time in a long time, for a real tactical mismatch between new AI-enabled drones and current Russian RFI-based counter-UAS systems.

Battlefield C-UAS sensors are becoming smaller:

and more mobile:

(Main image:Shutterstock)